The humanitarian sector is characterised by significant exposure to field-based and organisational stressors which can affect the health and wellbeing of practitioners. A review of the mental health status of humanitarian workers (Connorton et al. 2012) found they experience higher rates of anxiety, depression, and trauma symptoms than the general population. Prevalence indicators of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) within this population range from 8 to 43% and are higher than those observed among military and police personnel (Rose et al. 2002; Defence Health 2016; Skeoch et al. 2017).

Within the sector, mental health issues are associated with increased staff turnover and health costs, loss of institutional knowledge and less effective programmes (Webster and Walker 2009; Korff et al. 2015). It is unsurprising then that over the last decade, there has been an increase in the number of humanitarian organisations providing psychosocial support to staff, recognising that humanitarian contexts are likely to worsen mental health and that employers must protect their workers’ wellbeing.

However, there is an inequality in the provision and access of meaningful psychosocial support. Reference guidelines for psychosocial support in humanitarian contexts are produced in the global north for international staff. They focus on rest and recuperation (R&R), compensation for working in high-risk environments, and housing and transport support. In contrast, national and local staff are rarely entitled to additional leave for family or community commitments and are usually required to manage their own housing and transport.

Our new report, Making psychosocial support meaningful for national and local humanitarian workers, explores these inequalities and presents key opportunities for the sector to improve psychosocial support for national and local humanitarian workers

What is psychosocial support?

As outlined in IASC Guidelines, the composite term mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) is used to describe ‘any type of local or outside support that aims to protect or promote psychosocial well-being and/or prevent or treat mental disorder.’

The term ‘psychosocial’ refers to the dynamic relationship between the psychological dimension of a person and the social dimension of a person. The psychological dimension includes the internal, emotional and thought processes, feelings and reactions, and the social dimension includes relationships, family and community network, social values and cultural practices. ‘Psychosocial support’ refers to the actions that address both psychological and social needs of individuals, families and communities to promote wellbeing and resilience.

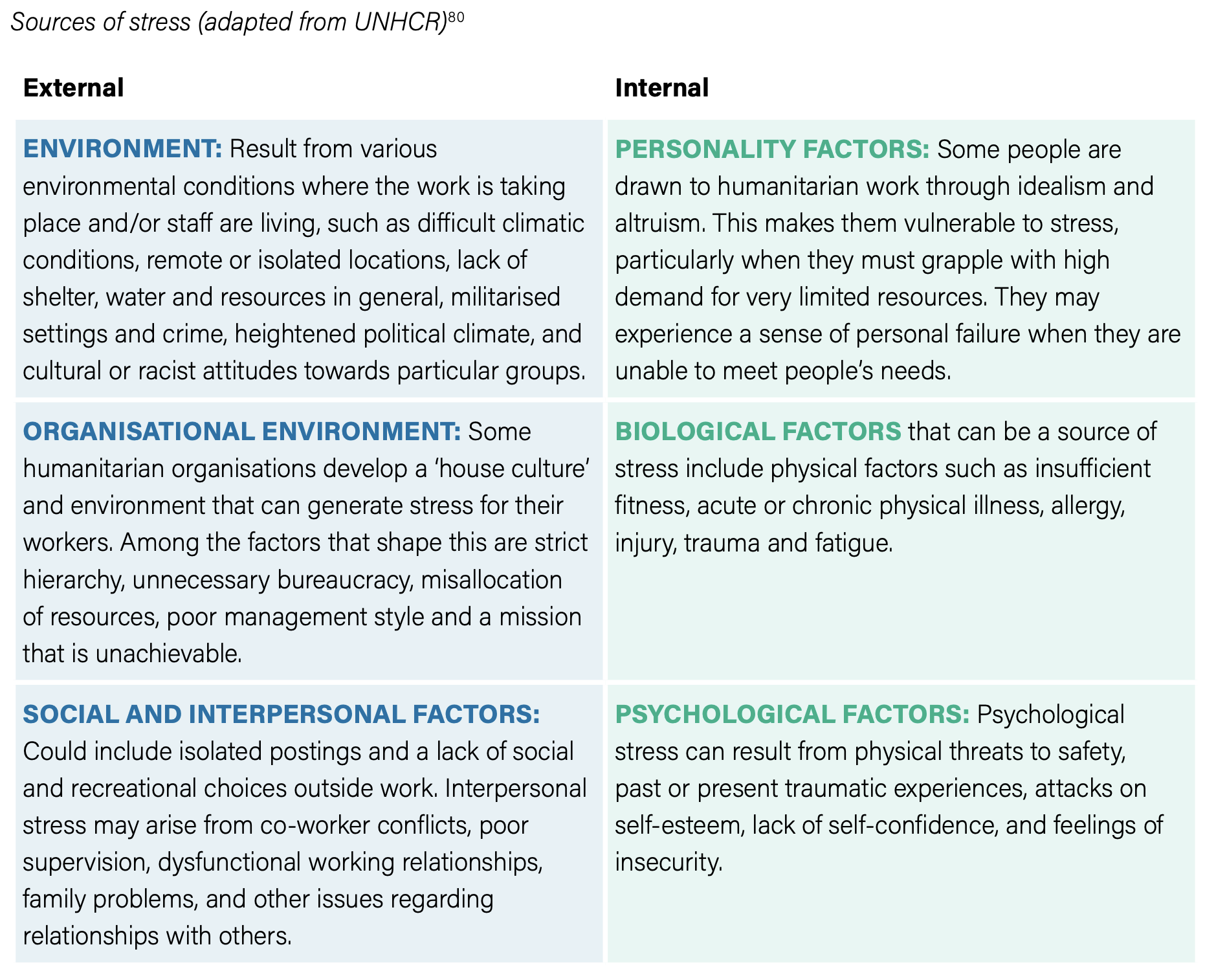

For humanitarian workers, there are specific stresses that trigger the need for psychosocial support. These can be external and internal and are experienced differently by international and national workers.

Why do national and local humanitarian workers need psychosocial support?

Evidence shows that national and international staff working in humanitarian agencies are exposed to different stressors that reflect structural inequalities in the sector. Many of the disparities relate to the daily and cumulative stresses generated within the workplace such as workloads and schedules, employment contracts with large differences in pay and benefits among colleagues, and power dynamics that reduce control over work and opportunities for career advancement.

A significant stressor is risk. National humanitarian workers are often perceived to be more familiar with the local context than their international counterparts, and thus able to better interact with and provide support to local populations. Therefore, they are often deployed in operations and assigned higher workloads with a greater degree of risk. National and local humanitarian workers are the targets of most attacks on aid workers. This is often because they are both aid providers and members of the affected community, meaning they may live in affected locations or nearby, and lack the mobility of international workers.

“National staff face unique stressors related to the nature of their work directly in the field, serving their communities. They grapple with the insecurity of their positions, as they are more susceptible to local conflicts and confrontations.”

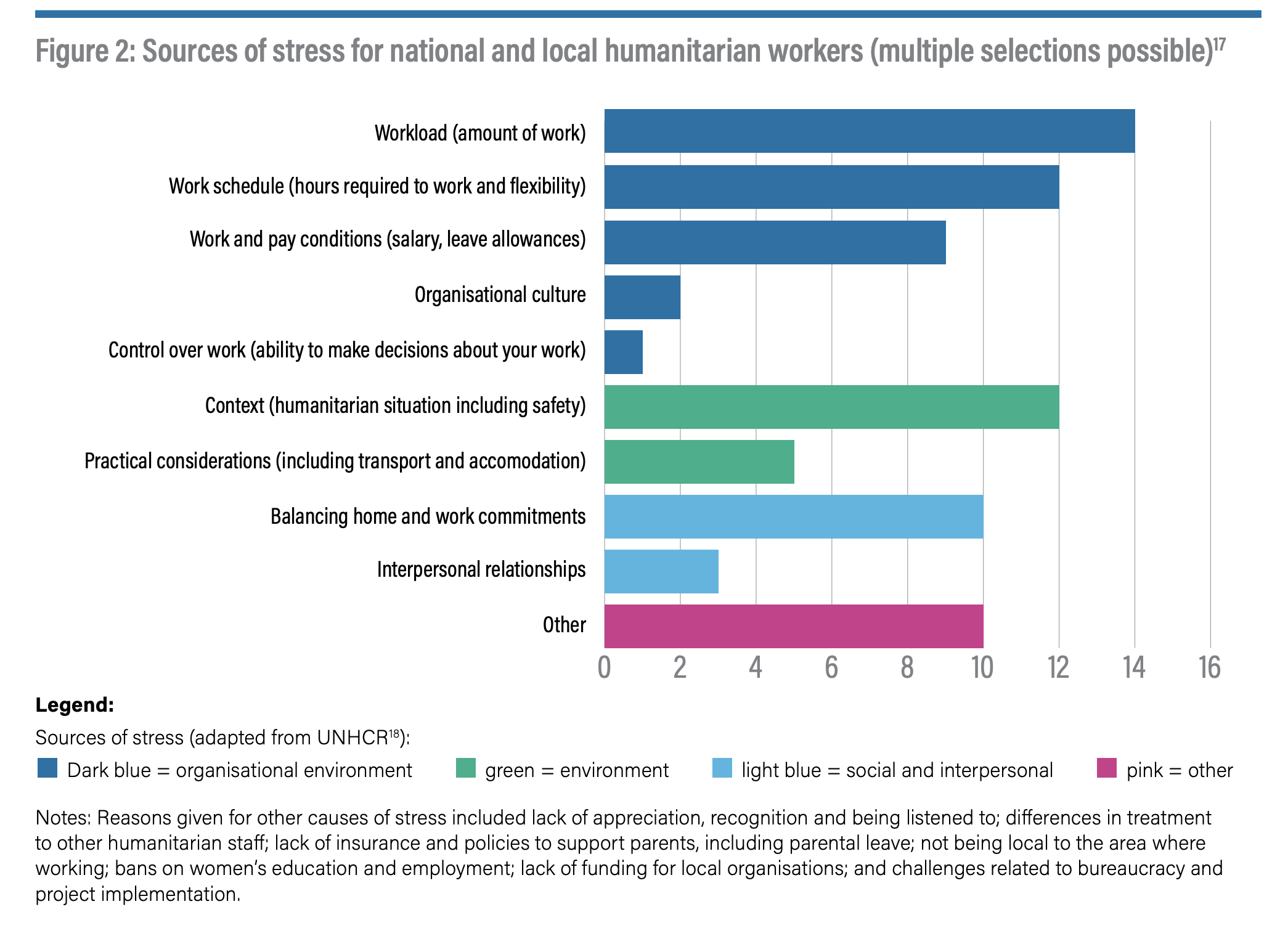

The Figure below provides a breakdown of the sources of stress reported by national and local workers as part of our research.

Does increased risk mean more psychosocial support?

Not yet. Drawing from research in Afghanistan and Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, this research indicates that the inequalities in psychosocial support for national and local staff differed from international staff in three key areas:

1) Availability: Humanitarian organisations provide broad psychosocial support, but national and local humanitarian workers receive relatively limited, less frequently tailored support.

“The psychosocial support provided to national staff compared to international staff […] differs in various aspects such as the amount, services available, relevancy, and accessibility. This often translates into better allowances, rest and recuperation opportunities, and other benefits for international staff.”

2) Accessibility: Psychosocial support provided by humanitarian organisations is not always accessible due to confidentiality concerns, stigma surrounding mental health, and practical barriers such as language and working within national systems.

“There is still a pervasive culture of confidentiality concerns among workers who fear their needs will be viewed as complaints. Although there may be systems in place to address these issues, workers may not be aware of them.”

3) Relevance and appropriateness: Most psychosocial support does not address the specific stressors experienced by national and local humanitarian workers and is not tailored to meet their needs.

“If you’re from that context, you live and work in it every day, if rolling from crisis to crisis, there’s no breathing space, there’s no R&R.”

This is echoed in broader research into differentiated barriers faced by national and local humanitarian workers seeking and accessing psychosocial support, with other factors including confidentiality and trust; duty of care; normalisation; experience; repercussions; self-reliance; stigma; and time (Eiroa-Orosa 2020).

How can this be improved?

Perhaps the easy answer here to is to direct humanitarian organisations back to the inequalities indicated above. Psychosocial support provided to national staff and partners can and should be improved by increasing availability and access, and ensuring it is contextually relevant and appropriate for the specific stressors experienced by them. However, this ignores the causes of these inequalities in the first place. Psychosocial support needs to take place in the context of broader processes to address inequalities embedded in the humanitarian system.

This research spotlights the importance of equity in the workplace to address this. Workloads, work schedules, pay, and conditions are key stressors. Reducing inequalities within the humanitarian system, particularly in relation to remuneration, benefits and career advancement, will also improve psychosocial wellbeing for national and local humanitarian workers.

Where there is a need for psychosocial support, it needs to be relevant. Organisations should consult national and local humanitarian workers to learn about the stressors that reduce their wellbeing and their preferred types of support. This should inform a range of options that consider contextual factors, language, culture and sources of stress, and to identify the barriers to accessing psychosocial support and how these can be overcome.

Finally, the research stresses that promoting psychosocial wellbeing requires ongoing research and advocacy to reduce the disparity between international staff and national staff.

For more information about this research or support in implementing changes in your own organisation, please contact the research team: info@humanitarianadvisorygroup.org