Women have not yet achieved parity in the humanitarian world. This applies, sadly, to women in humanitarian action, to women in humanitarian media, and to women in the context of COVID-19. Now, a new measurement framework developed by Humanitarian Advisory Group and UN Women has shown that, even when women and women’s rights organisations (WROs) are operationally active and supported to coordinate, advocate, and grow, their lack of access to the spaces where decisions are made continues to prevent transformative change that serves the interests of women and girls.

The framework measured four domains: transformative leadership, safe and meaningful participation; collective influencing and advocacy; and partnership, capacity and funding. It was piloted in the Philippines, where the impacts of COVID-19 have been among the most severe in Southeast Asia. The government declared a “state of calamity” on 16 March 2020, but public health measures have struggled to contain the spread of the disease or prevent it from overwhelming the health system. The COVID-19 Humanitarian Response Plan in the Philippines was released in May 2020, and updated in August 2020, indicated that over 40 million people would need assistance during the pandemic.

Despite a challenging context, including gendered inequalities and conflict, diverse women and women’s rights organisations have played an important role during the pandemic. With the health care sector overwhelmingly staffed by women, women have been paramount in the response, shaping what it looks like on the ground. Women’s rights organisations have been active in civil society coordination forums and, to some extent, local government forums. International partners have helped to strengthen institutional capacity of WROs during the pandemic, as seen in support for the Women in Emergencies Network (WENet). Advocacy is another area where collaboration between agencies has been particularly strong, with 69% of WRO respondents to our survey agreeing or strongly agreeing that international partners and donors had adequately supported their organisation to advocate for diverse women during the response.

However, our research highlighted some stark differences in perceptions of the response. When asked whether COVID-19 response plans and programs adequately addressed gender-based issues, only 14% of women’s rights organisations agreed or strongly agreed – a proportion that rose to 44% among other humanitarian actors. The gap was even greater when we asked whether the needs of diverse women had been addressed adequately: 14% and 51% respectively.

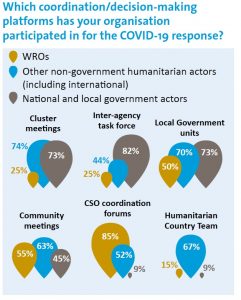

Tellingly, of 30 sets of notes from different COVID-19 meeting forums at the national and humanitarian coordination level that we studied for our research, only nine (30%) mention gender and/or women and girls. This lack of attention is also apparent in the absence of women’s rights organisations from key coordination forums (see graphic below). As a result, WROs’ advocacy successes have been ad hoc and their influence on the response itself has been limited.[1]

We did not set out to do an evaluation of the response, so we cannot, on the basis of the evidence we have, make claims about its quality or outcomes overall. Nonetheless, what we see is an emerging picture of a response that relies on women’s contributions but does not represent their input or give consideration to their leadership. As one of our interviewees put it: “I think it was not even considered at all. That’s how I feel about the overall response. There was no consideration in terms of the gender responsiveness of the programs.”

The failure to convert the operational engagement of women and WROs into strategic leadership means that time is spent fixing gaps in practice that could have been avoided with better policies, then retrofitting those policies to match the more inclusive practice.

What can be done? In addition to ensuring that WROs’ activities are properly funded – a simple consideration but rarely undertaken – our research identified a number of steps converging around three main areas:

- Holding open discussions around impacts of changes to funding, program implementation, and no-cost extensions on WROs and their objectives.

- Actively promoting the participation of WROs in key forums for coordination and advocacy, by inviting them or calling for their involvement and by supporting them to prepare for these meetings.

- And as part of this, engaging with WROs to better understand barriers to participation in forums and how partners, donors and other humanitarian actors can offer support them – conversations that need to be held repeatedly as the response evolves.

Transformative leadership in the humanitarian sector requires access to specific decision-making spaces where policies are determined, decisions are made, and strategies are set. The absence of WROs and their voices in these spaces reduces their ability to lead or influence national approaches to humanitarian responses. Until other actors make it their own responsibility to support more equitable access to strategic spaces, the potential for women and other less powerful groups to contribute to leadership will remain just that: potential.

[1] The GBV sub-cluster was last activated in 2014 during the Haiyan Response and resulted in numerous national policies and standards that operationalized survivor-centered GBV response; such as Women-Friendly Space Guidelines, Training Manual for Gender- Responsive Case Management.. During the COVID-19, the GBV sub-cluster was reactivated at the National Level in December 2020, but UNFPA, as the co-lead, supported DSWD in GBV preparedness and response activities prior to it, even without formal activation. This sub-cluster and the protection cluster were seen as critical for a for increased WRO representation over time.

Photo by John Alvin Merin on Unsplash